ELEMENTAL FORMS: NOTES ON TOPIARY AND SCULPTURE

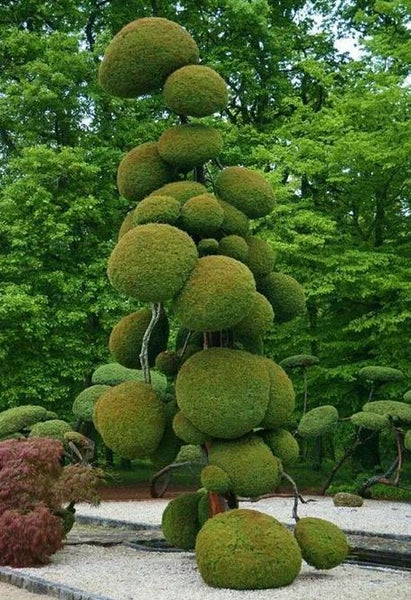

Traditional Japanese gardens are environments of stillness and grounding, they echo the shapes of the land, creating a contemplative sense of harmony that is integral to the Eastern gardener’s practice.

Microcosms of the surrounding country itself, the gardens contain organic shapes and flowing lines – created in a manner known as cloud pruning – that visually tie to mountains, skies, and waterfalls. This subtle yet skilful styling to the surface of the landscape enhances rather than controls the plant’s latent energy and natural asymmetries, making room for time’s unstoppable advance.

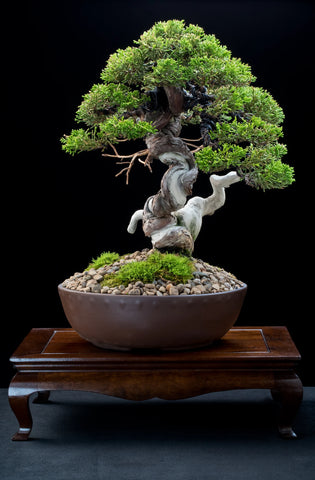

Bonsai trees intensely evoke the natural realm beyond itself. In a push pull, ongoing and lifelong dialogue between tree and bonsai master, roots are rigorously restricted, and branches are fastidiously pruned to further connect the tree to its natural impetus and life force.

Topiary in the European sense is said to have been invented by a friend of the ancient Roman emperor Augustus and is known to have been practiced in the 1st century CE. Although early references to topiary are lacking, the art probably evolved over a considerable period from the necessary trimming, pruning, and training of trees. Concurrently the Chinese and Japanese were also developing pruning as an art form.

Levens Hall in Cumbria is home to the world's oldest topiary garden, designed by Monsieur Guillaume Beaumont and established from 1694.

Classically formal and geometric, European topiary revels in scores of pyramids, spirals, and top hats. Pruners are wielded to create strong lines and impressive slopes of tumbling die that call to mind a cubist landscape by Braques or Picasso.

"There is no room for indecision in the topiarist’s vocabulary, nor sentimentality – a certain degree of dictatorship is called for, as is enthusiasm and above all an understanding of your role in the relationship." Jake Hobson [1]

Some forms in the Western topiarists vocabulary have taken on more discreet and deliciously organic characters that blend seamlessly into their surroundings and are akin to the practices in the East.

In these surreal environments, forms playfully slip in and out of view, rolling back to the natural world from whence they came.

To prune is an exercise in potential and anticipation, to draw out latent shapes nestled in the earth’s surface, and to create forms that speak to and enhance the essence of the landscape.

As topiary is a collaboration with the nature – an ongoing dialogue between the pruner and the plant – the sculptor and their materials exist in dynamic equilibrium. The sculptor’s materials are not static, they are alive and constantly though subtly changing.

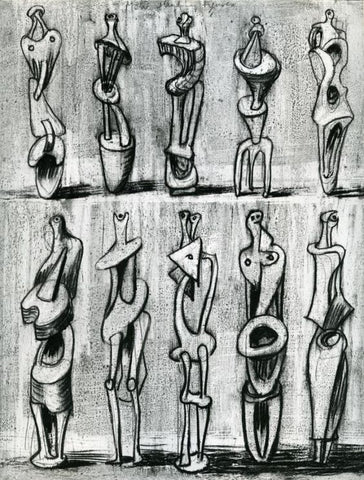

Henry Moore’s output was rooted in his relationship to the natural world and his undying love of rugged landscape. He was fascinated by natural forms; clouds, trees and their roots, and mountains, which he saw as the wrinkling of the earth’s surface. The artist carved his forms to release negative space; in removing material, he revealed the found and elemental forms of his sculptures.

"I think a sculptor is a person who is interested in the shape of things […] a person obsessed with the form and the shape of things, and it’s not just the shape of any one thing, but the shape of anything and everything: the growth in a flower, the hard, tense strength, although delicate form of a bone; the strong, solid fleshiness of a beech tree trunk. […] They’re all part of the experience of form and, therefore, in my opinion, everything, every shape, every natural bit of form, animals, people, pebbles, shells, anything you like are all things that can help you to make a sculpture." Henry Moore

The tradition of subtractive sculpture and negative space finds traces in the Italian Renaissance. Michelangelo carved and chipped at Carrera marble to free figures he imagined existing inherently in the mass of stone.

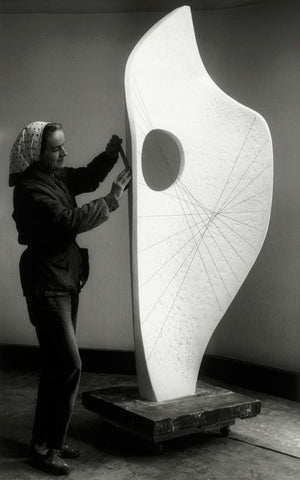

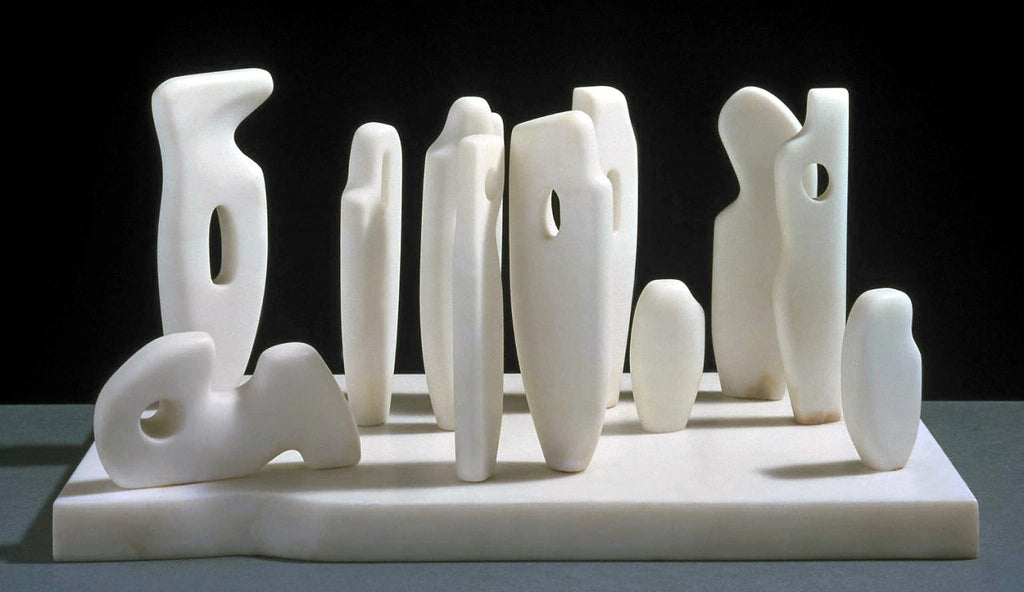

Barbara Hepworth equally engaged with the carving process, engaging in the search for pre-existing shapes discovered through a combination of intuition and deep sensitivity for the material.

"The sculptor carves because he must. He needs the concrete form of stone and wood for the expression of his idea and experience, and when the idea forms the material is found at once. [...]." Barbara Hepworth [2]

[1] Jake Hobson, The Art of Creative Pruning: Inventive Ideas for Training and Shaping Trees and Trees, Timber Press, Portland, 2011

[2] Extracts from ‘Barbara Hepworth – “the Sculptor carves because he must”, The Studio, London, vol. 104, December 1932, p.332

Words by Isabella Bragoli