NAUM HOUSE BATHROOM ROUNDUP

As designers, we are constantly researching and looking back into history to find the most exquisite solutions that combine function and aesthetics. The bathroom, in particular, has evolved considerably with the advent of infrastructure in the 20th century and it is a room that must accommodate an array of functions, including those considered most private to the modern personage. Here is a roundup of our studio's favourite bathrooms of all time:

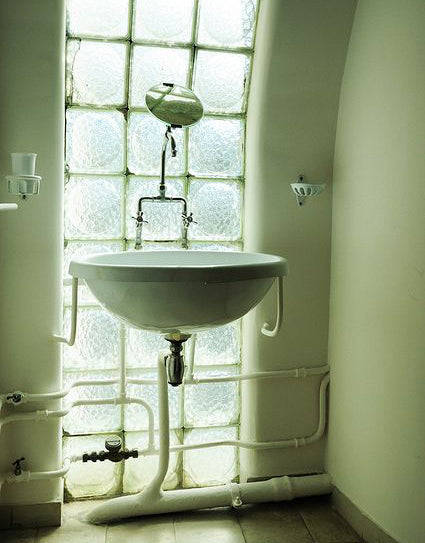

Le Corbusier, Studio Apartment, Paris, 1931-1934

At 24 rue Nungesser et Coli, on the top two floors of the Molitor apartment block, you will find the studio-apartment of Le-Corbusier, where he lived from 1934 until his death in 1965. Designed between 1931 and 1934 by Le Corbusier, in collaboration with his cousin and associate, Pierre Jeanneret, the building offered Le Corbusier the opportunity to test the validity of his urban proposals. According to Le Corbusier’s Modulor model, an architectural concept of his own invention, whereby a housing unit should provide maximum comfort in the relationship between man and his living space.

The wall of light was created with a grid of thick, mottled Nevada glass blocks, impressed with a flattened bubble shape. The bathroom is tucked into the cove of the vault, and the glass block arches inward – a space that would be typically reserved for servant’s quarters.

Armand Albert Rateau, Jeanne Lanvin's Bathroom, Paris, 1924-1925

In 1920, the great fashion designer Jeanne Lanvin purchased 16 Barbet-de-Jouy in Paris, a mansion formerly owned by the Marquise Arconati-Visconti. For the private apartment, designer Armand Albert Rateau created the luxurious schemes for the bathroom, bedroom and boudoir in 1924-25. The two shared a taste for quality and precious materials and the extraordinary luxury of the bathroom reflects the classical and oriental influences on Rateau’s style.

The walls are covered in stucco, with a plaster low relief of a forest scene in the bath alcove, the sanitary fittings and built-in cabinets are a beige Hauteville marble. The marble floor tiles form a geometric design, with a black marble path leading from washbasin to bath. Floral and fauna appears throughout the room, with patinated bronze lights and faucets shaped in the image of pheasants, daisies and pine cones. Rateau’s attention to every little detail recalls Lanvins’ own fastidiousness in her work - alongside her fashion designs, she created cosmetics and perfumes.

Karl Lagerfeld, Atelier Apartment, Rome, 1986

“There is something restrained, a little puritan in this room. It is reminiscent of the strange relationship that the Northern Europeans had with Italy, a mix of fear and fascination.” - Karl Lagerfeld

Since working for Fendi, Karl became a regular visitor to Rome and in 1986 he took a former artist’s studio as his atelier apartment. The area had previously been the site of a colony of artists from northern Europe who spent time in Rome as part of their Grand Tour, even Caravaggio had once had an atelier here, near the Vitolo del Divino Amore. Lagerfeld took this as his inspiration, drawing on northern European painting, such as the work of Danish artist Christian Bang, and a neoclassical architectural style.

In the bathroom, a trompe-l'œil effect of wood panelling was created by painting the walls in faux bois. The room is decorated with plaster reliefs, ornaments and medallions. The wooden spiral staircase leads up to the master bedroom and uses the same faux bois paint effect to blend seamlessly into the walls. Fortuny fabrics, a mountain scape painting, Wiener Werkstätte furniture, a stack of plush ivory towels, embroidered with a simple black KL monogram complete the space.

Eileen Gray, E-1027, Roquebrune-Cap-Martin, 1926-1929

Architect and furniture designer Eileen Gray created Villa E-1027 with her then partner, Romanian architect Jean Baodvici, between 1926 and 1929. It was her first architectural creation. Gray was a pioneer who carved out her space in the hostile, male-centric world of Modernism. After finding success as a furniture designer, she turned to architecture and with no formal training, created an iconic building that reinstated warmth and comfort as principle tenets of Modernist design. E-1027 served as a vacation house, experiment, and prototype lab, allowing her to explore the use of ordinary industrial materials in an extraordinary way.

As she said herself, the bathtub “is a very ordinary one, but it has been covered in an aluminium sheet that gives it a pleasant aspect and brings some gleam to the whole ensemble”. The glazed black tiles continue the theme of reflective surfaces, whilst the bidet doubles as a stool with a bright orange foam rubber cover.

Oliver Hill, North House, London, 1930s

In 1933, Country Life Magazine published North House, the London townhouse of Mr and Mrs Robert Hudson. Hudson was an MP at the time and he and his American wife, asked Oliver Hill to create their home, including this fabulous bathroom.

Using beveled mirror strip, Hill created the reflective fluted wall that served a dual purpose of diffusing light around the room. The space features a luxurious mix of classical details with expensive materials and furnishings, such as fluted and flared oval bath, lined with silver mosaics and the ceiling above of illustrator and artist Edward Bawden’s seaweed wallpaper. It is a thoroughly modern interpretation of the boudoir.

Whilst Hill originally began his career in the Arts & Crafts movement and worked as an apprentice to Edwin Lutyens, by the 1930s, his interest shifted towards modernism and he became renowned for luxurious interior decoration in the Vogue Regency style with heavy Art Deco themes running throughout. Interior decorator Syrie Maugham asked him to work alongside her on the redesign of her own home, No. 213 King’s Road, and she often used a similar look in her bathroom designs, filling the room with patinated mirrors.

Jean Lafont, Mas des Hourtès, Camargue, 1945

Eclectic and refined, the interiors of Jean Lafont’s home in Camargue reflect the man himself - a celebrated manadier and founder of the infamous La Churascaia nightclub, where the elite flocked. In 1945, he settled in the Petite Camargue, at Mas des Hourtès, where he transformed the property of the Viscountess Marie Laure De Noailles. The house became an institution for the arts and entertaining, with guests such as the Kennedys, Jackie and Aristotle Onassis, César, Jean-Claude Brialy, Sophie Calle …

The setting for such occasions showcase the many-faceted tastes of Lafont, ranging from troubadour art to Soviet realism, with touches of Art Nouveau and Art Deco. We love the dominant sandstone tub combined with an eclectic selection of Art Deco furniture.

Lina Bo Bardi, Casa de Vidro, Sao Paulo, 1951

Lina Bo Bardi (1914-1992) was an Italian born, Brazilian Modernist Architect. She moved to Brazil in 1946, to work and live in Sao Paulo. Casa de Vidro (aka The Glass House) was her first official work as an architect as well as her personal home where she hosted the great thinkers and cultural figures of the day. It has become one of the most iconic glass houses of Modern architecture, marked by its striking glass façade that creates an illusion of floating within the surrounding jungle. An early example of reinforced concrete in domestic architecture, the building consists of two reinforced concrete slabs supported by pilotis which allow it to be embedded into its uneven, and dense vegetational environment rather than set onto the ground.  Bo Bardi came from the architectural current developed in Italy in the 1920s and 1930s, known as Italian rationalism, and Casa de Vidro demonstrates her first attempt at finding a Brazilian language for the Italian modernism in which she had been trained. She was teaching industrial design at the time, evident in the style of the bathroom with a graphic quality to the lines.

Bo Bardi came from the architectural current developed in Italy in the 1920s and 1930s, known as Italian rationalism, and Casa de Vidro demonstrates her first attempt at finding a Brazilian language for the Italian modernism in which she had been trained. She was teaching industrial design at the time, evident in the style of the bathroom with a graphic quality to the lines.

George Nakashima, Sanso Villa, Pennsylvania, 1977

George Nakashima was an American craftsman, architect, and furniture designer, who is regarded by many as the father of the American craft movement in the mid-20th century. His work combined international styles, modern influences and Japanese craft traditions. Between 1960-1975, he designed and built a series of houses in New Hope, Pennsylvania, the last of which is the Sanso Villa or “reception house”. Intended as his retirement home, it served as a guesthouse, and demonstrates how Nakashima bridged modern visions from the West with Japanese craftsmanship. The wall material, called “kyo-kabe”, was imported from Kyoto, Japan and was combined with exposed wood beam ceilings.

In the bathroom, he created a playful interpretation of a traditional soaking tub, with penny tiles forming a mosaic design that incorporates his grandchildren’s names and drawings.

Geoffrey Bawa, De Soysa House, Colombo, 1985-1991

Sri Lankan architect Geoffrey Bawa created this house for his old friends Cecil and Chloe de Soysa, who deemed their old family home too large with the children departed. The house, in downtown Colombo, belongs to his wider canon of tower houses, and demonstrates Bawa’s approach of Tropical Modernism, a new style of vernacular architecture suited to the hot, humid climate of Sri Lanka.

The De Soysa house was glazed with dark anodized aluminium, and the narrow frames melt into the background of plant life. The contrast between these frames and the white walls, along with the simplicity of detailing throughout represent the move towards minimalism to which Bawa was increasingly drawn.

In a note to Chloe, Bawa wrote “The roof is part pergola and part open to the moon and stars – and a view over the neighbouring trees. Hope you like it!” 6 July 1985