IKEBANA AND ITS ITERATIONS IN WESTERN CONTEMPORARY ART

Poetry made manifest through petals, earth, and blooms, ikebana is a sensitive and refined form of Japanese flower arranging aimed at intimately manifesting the botanist’s inner state of mind.

"Poetry is the expression in words of the unknowable and invisible beyond this world, and ikebana is also a way of giving form to invisible things inside us, with the aid of plants’ innate power." Akane Teshigahara [1]

Ikebana is a ritual steeped in sacred ancestral Japanese tradition. In the Nihon Shoki, when the adored Princess Izanami died at a young age, her people started to create flower arrangements to honour the place where she was buried and ‘console the soul’ of the woman they revered.

With the introduction of Buddhism in Japan, ikebana began to develop alongside Buddhist and Zen practices – its origin is the kuge (供華), offerings of flowers made to Buddha. Speaking to the animistic notion that god resides in all things natural, the arrangements harmonise the subtle relationship between humanity, the natural world, and the ineffable spaces in-between.

Ikebana also exists everyday life – a symbol of Japanese hospitality that plays an integral part of daily life. The distinct separation between the rituals of artistic, spiritual, and daily life don’t really exist in the same way in Japanese culture as they do in the West. A sense of spirituality underpins supposedly mundane tasks – drinking water or tea, snipping the blooms to an ikebana arrangement.

The practice has traditionally revolved around several main principles:

- Representing the artist’s inner-most nature

- The formation of lines with plant stems

- An adherence to visual minimalism

- Three-pointed, scalene structures

- A preference for found forms in place of those that appear arbitrarily constructed.

- Seasonal appearances

- A process of removal rather that building to reach the final composition

Today, contemporary artists are heralding an avant-garde ikebana movement. Turning away from the staunch adherence to traditional mores, the practice’s core principles are, instead, used as a springboard from which greater artistic exploration can be reached.

Cerith Wyn Evans

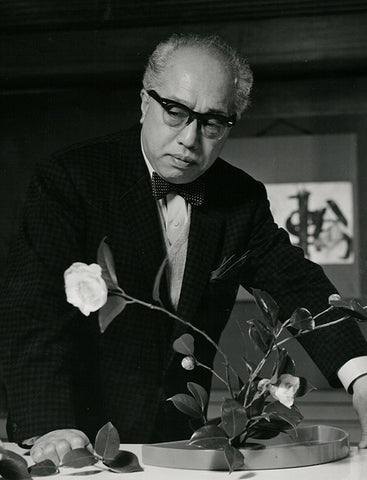

The Welsh-born artist, Cerith Wyn Evans, embodied the ethos of the avant-garde ikebana movement in an exhibition that took place in Isamu Noguchi’s Garden at Sōgetsu in 2023.

Founded in 1927 in the spirit of modernist experimentation, Sōgetsu was as the first ikebana school to recognise the practice as a creative art. Noguchi’s garden, ‘Heaven’, was created in the lobby with stones, and flowing water; natural light cascades from the ceiling and changes throughout the day and between seasons.

Evans transformed the garden into a type of stage set with a mise en scene of various installations. Pine trees, floor to ceiling pillars of lights, automated crystal glass flutes, and neon text relating to the Japanese translation of Marcel Proust’s In Search of Lost Time paid homage to what we don’t necessarily see with our eyes and the ‘texture’ of time itself. The deeply phenomenological invocation of the invisible recalls the way in which ikebana arrangements stand as a referent for deep-seated feeling and the conflation of space and time.

"I’ve always tried to invoke a level of complexity… there are things immersed within the texture of the work that allude to other spaces and possibly other times." Cerith Wyn Evans

Camille Henrot

In the exhibition ‘Is it Possible to Be a Revolutionary and Like Flowers?’ in 2012, Camille Henrot turned to the language of ikebana to ‘translate’ books from her personal library into floral sculptures.

Henrot followed the Sogetsu tradition, mostly using empty space, asymmetrical compositions and seasonal materials as crucial design elements.

For the artist, an ikebana arrangement conceptually mirrors a book – both single objects that contain multitudes of thoughts and provide meditative refuge from the outside world.

Carol Bove

In Carol Bove’s work, plants are not directly used as artistic medium; however, the artist’s eloquent and visually understated assemblages speak to the ikebana process.

In a shared way of arranging disparate objects, forms are welded and woven together, creating new possibilities for traditions previously considered to be exhausted and refer to subjects outside of their originally perceived meaning.

“Already existing materials are combined to create a new unity. The artist is constantly bound by the laws of the material itself, or at least he must take them into consideration. Whereas dead material, may be handled heartlessly, flowers demand careful attention otherwise they will fade too quickly.” Shusui Komoda [2]

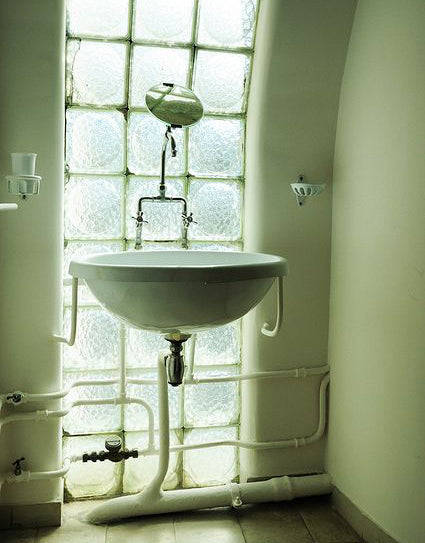

Harry Dodge

Junkyard ikebana – a surprising but masterful manifestation of the art – takes shape in Harry Dodge’s sculptures. Dodge’s works draw together unlikely materials – pipes, plywood, offshoots of discarded hardware – to form unwieldly bouquets.

They are visual emblems of irony – sculptural bouquets that possess the ability to hold opposites in harmonious tension.

Dodge’s sculptural exhibitions invoke Maurice Merleau-Ponty’s essay The Intertwining—The Chiasm (1964) and the philosopher’s consideration of what the artist describes as ‘the flesh of the world . . . this charged space, this mucky tension (love?) between organisms.’

[1] Article published in Fun Palace - Akane Teshigahara: Seven Questions for the lemoto of the Sogetsu School of Ikebana - 22 September 2022.

[2] excerpt from Ikebana Spirit and Technique, written by Shusui Komoda and Horst Pointner.

Words by Isabella Bragoli